Note : l’essentiel du texte est issu du rapport de l’ACPR mentionné en référence. Cet article vise à mettre en exergue quelques extraits de ce rapport afin de pouvoir mieux appréhender l’essentiel de l’étude.

1. L’analyse des risques financiers dus au changement climatique

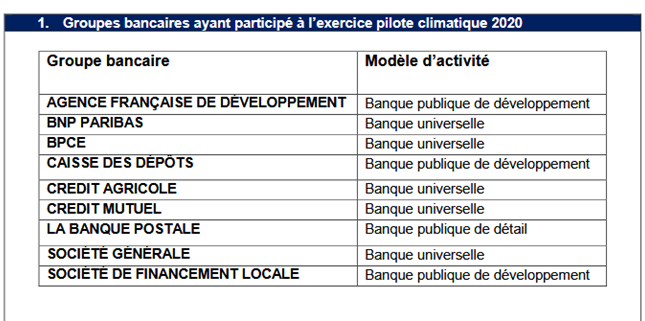

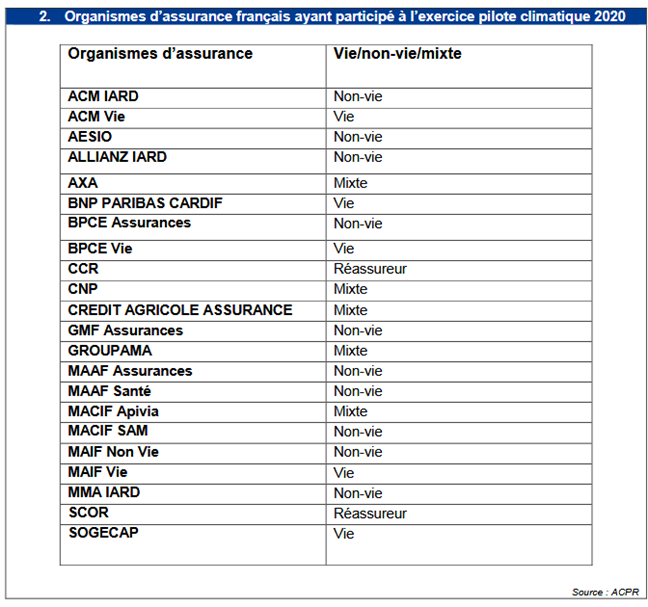

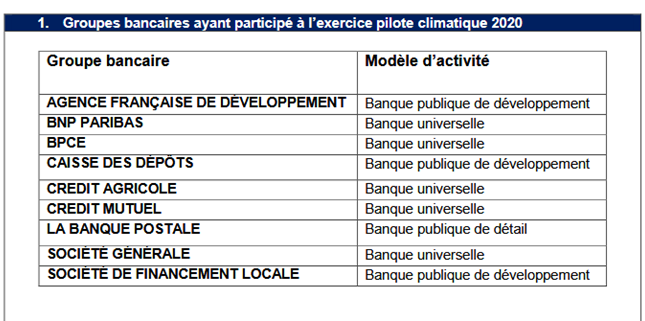

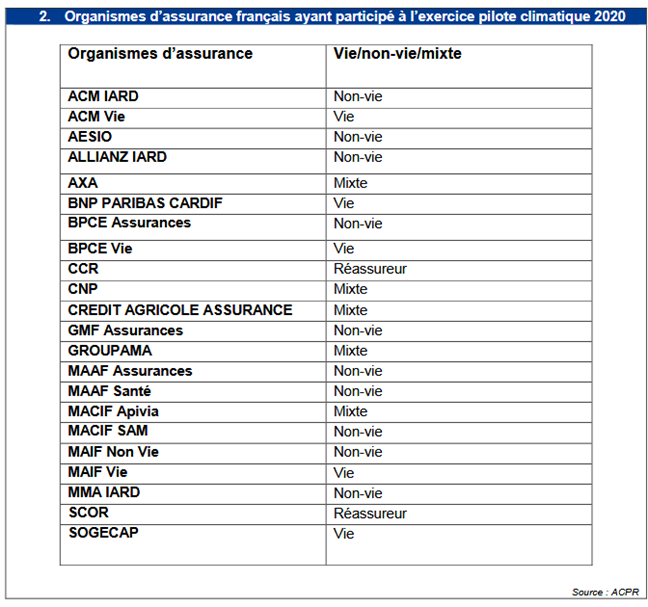

De juillet 2020 à avril 2021, l’ACPR a conduit un exercice de stress test pilote sur l’impact du changement climatique (risques physiques et de transition) sur les risques financiers du secteur financier. L’exercice a mobilisé les acteurs des groupes bancaires et d’assurance.

L’horizon sur lequel les risques sont évalués est de 30 ans et plusieurs scénarios ont été implémentés sur différents secteurs économiques dans une vision dynamique des bilans des institutions financières. Ces travaux s’inscrivent dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre de la lutte contre le dérèglement climatique et la promotion de la transition énergétique et la croissance verte, en ligne avec l’Accord de Paris en 2015.

Cet exercice d’évaluation des risques financiers induits par le changement climatique sera reconduit régulièrement. Le prochain exercice de l’ACPR devrait se tenir en 2023/2024.

2. Analyse de l’impact du risque de transition énergétique

2.1. Trois Scénarios de stress tests de transition énergétique

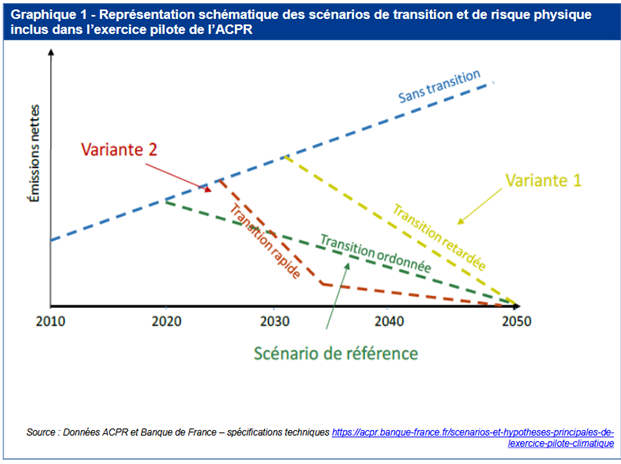

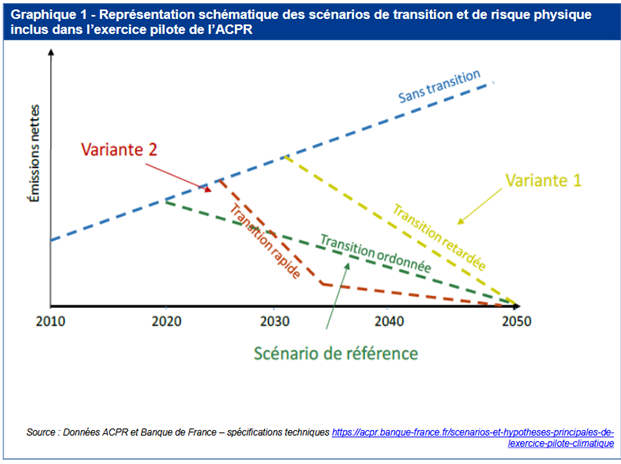

Les scénarios de transition intègrent un scénario de référence, correspondant à une transition ordonnée, et deux scénarios de transition désordonnée.

Le scénario de référence choisi par l’ACPR est le scénario le plus favorable bien qu’il s’appuie déjà sur une progression importante du prix du carbone, entrainant des changements importants de l’économie.

Le premier scénario adverse de transition désordonnée est celui d’une transition tardive. Il suppose que l’objectif de réduction des émissions de gaz à effet de serre n’est pas atteint en 2030, ce qui exige la mise en place de mesures plus volontaristes. Il suppose que les technologies de séquestration du carbone sont moins efficaces que prévu pour compenser les émissions. Il repose sur une hypothèse de très forte hausse du prix du carbone en 2030 pour maintenir l’objectif de neutralité carbone en 2050. Celui-ci passe en effet de 14$ par tonne de CO2 au niveau mondial en 2030 à 704$ en 2050. Cette augmentation se traduit par une série de chocs hétérogènes sur les secteurs d’activité et entraîne une très forte hausse des prix réels de l’énergie (+125 %) sur cette période en France.

Le second scénario adverse de transition désordonnée est celui d’une transition accélérée. Il associe une forte hausse du prix du carbone, qui atteint 917$ par tonne de CO2 en 2050, et une évolution moins favorable de la productivité que celle retenue dans le scénario de référence à partir de 2025. Les technologies de production d’énergies renouvelables sont en outre moins performantes que prévu, ce qui implique des prix de l’énergie plus élevés et des besoins additionnels d’investissements.

2.2. Résultats des stress tests de transition énergétique

2.2.1. Bilan dynamique

L’hypothèse de bilan dynamique, permet aux établissements de prendre des décisions de gestion en réponse aux différents scénarios analysés et de réallouer leur portefeuille entreprises entre les différents secteurs d’activité à partir de 2025. Cette hypothèse permet d’analyser les stratégies de long terme déployées par les établissements.

Le secteur « électricité et gaz » qui bénéficie de la transition dans les scénarios, voit sa part dans les expositions totales augmenter fortement, alors que dans le même temps, le secteur des industries extractives, qui lui est négativement impacté, voit sa part diminuer dans les expositions entreprises des banques.

Deux grands types de stratégies apparaissent :

- Celles de certains établissements qui font le choix de financer l’économie dans son ensemble et qui, pour cela, alignent la structure de leur portefeuille de crédits sur la structure sectorielle de l’économie. On ne peut cependant totalement exclure que ce choix reflète une stratégie passive d’adaptation. Il est également possible que ce choix résulte de la difficulté pour certains établissements de se prononcer sur des actions de gestion stratégique à un horizon aussi éloigné.

- Celles des banques qui ont conduit une analyse secteur par secteur, afin de choisir sur base plus fine, les réallocations à effectuer. Ce choix peut être conditionné par :

- L’existence d’engagements publics ou d’une politique sectorielle déjà arrêtée.

- La volonté d’accompagner des secteurs clefs dans la transition énergétique.

- La pression de la société civile pour réduire certaines expositions sectorielles.

- Une divergence d’analyse sur la dynamique sectorielle à l’horizon 2050 avec les scénarios fournis par l’ACPR.

2.2.2. Risque de crédit

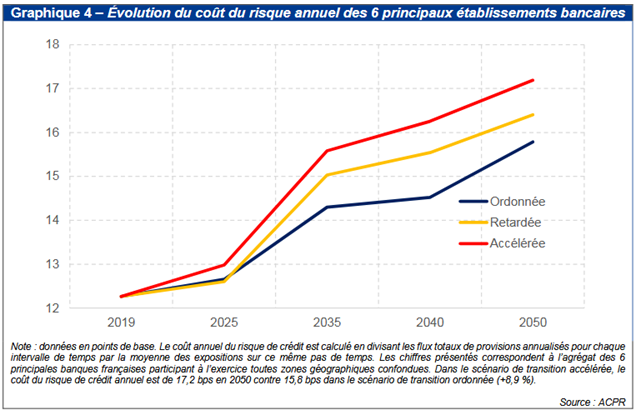

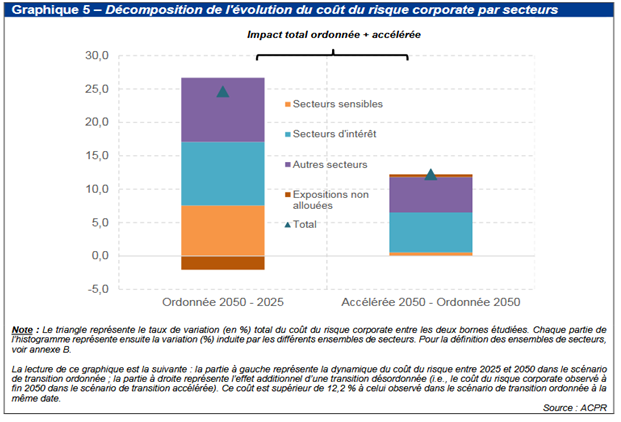

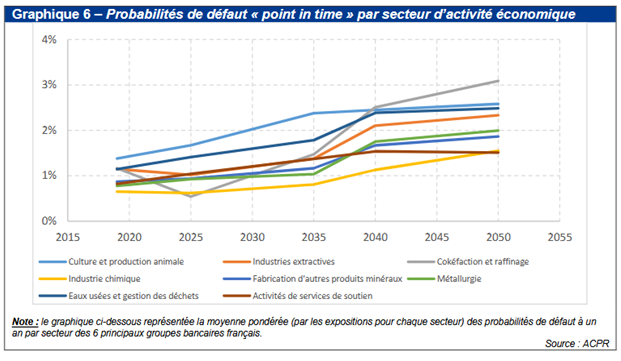

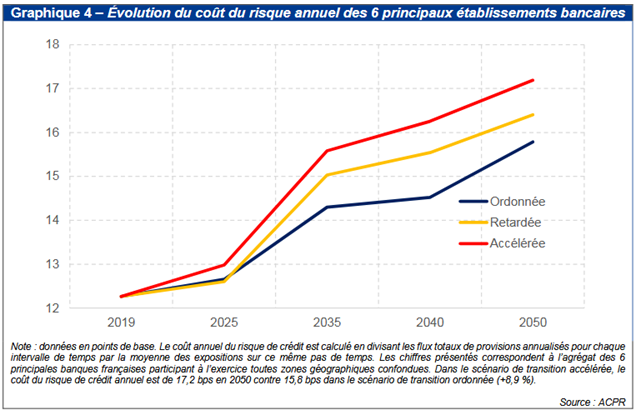

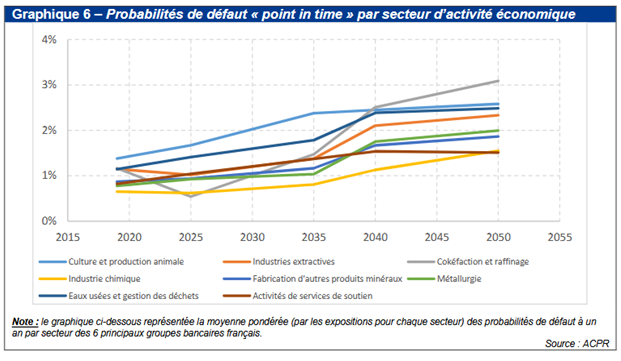

L’analyse porte sur des projections relatives au risque de crédit dans les différents scénarios de transition. L’indicateur retenu est le cout du risque de crédit annuel.

Les analyses tendent à confirmer qu’une transition désordonnée (et même, une transition ordonnée), impacte significativement le risque de crédit des établissements bancaires. L’ampleur de cet impact apparaît néanmoins inférieure à celle observée dans le cadre des exercices de stress-tests biannuels de l’EBA. La raison est liée au fait qu’aucun des scénarios de transition envisagé ne s’accompagne d’une baisse du PIB, contrairement au cadre usuel de stress-tests réglementaires.

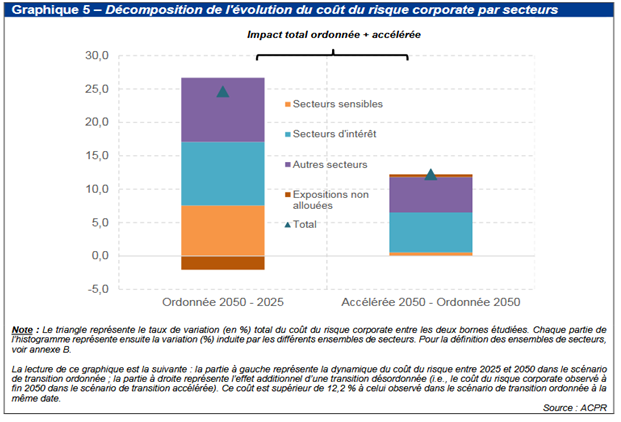

Les secteurs sensibles à la transition énergétique sont représentés par les secteurs :

- Culture et production animale, chasse et services annexes.

- Industries extractives.

- Cokéfaction et raffinage.

- Industrie chimique.

- Fabrication d’autres produits minéraux non métalliques.

- Métallurgie.

- Collecte et traitement des eaux usées, collecte, traitement et

- Élimination des déchets, dépollution et autres services de gestion

des déchets.

Les secteurs d’intérêts relativement à la transition énergétique sont représentés par les secteurs :

- Industries alimentaires, fabrication de boissons, fabrication de

produits à base de tabac. - Fabrication de produits en caoutchouc et en plastique.

- Fabrication de produits métalliques, à l’exception des machines et

des équipements. - Industrie automobile.

- Production et distribution d’électricité, de gaz, de vapeur et d’air conditionné.

- Construction.

- Commerce et réparation d’automobiles et de motocycles.

- Commerce de gros, à l’exception des automobiles et des motocycles.

- Commerce de détail, à l’exception des automobiles et des motocycles.

- Transports terrestres et transport par conduites.

- Transports aériens.

- Hébergement et restauration.

- Activités de services administratifs et de soutien.

2.2.3. Risque de marché

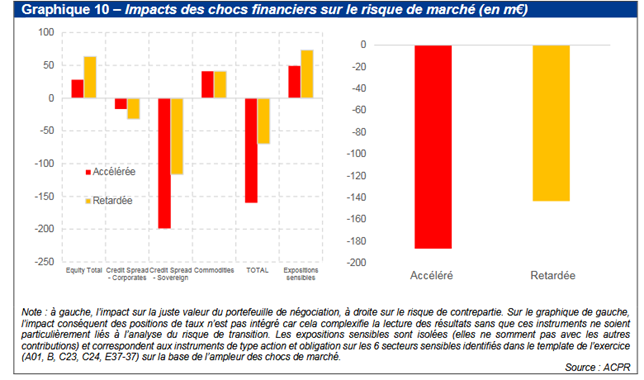

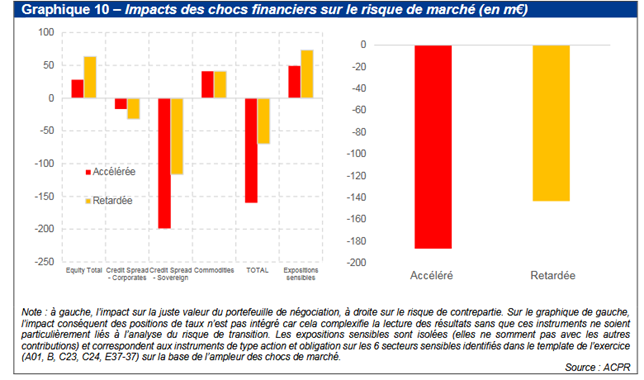

Le risque de marché constitue la seconde catégorie de risques faisant l’objet de projections de pertes de la part des établissements bancaires. Celui-ci est décomposé en deux sous-catégories :

- La réévaluation du portefeuille de trading, à la suite d’un choc instantané de marché induit par la valorisation des actifs sur la base des scénarios de transition anticipés.

- L’impact de ces chocs de marché sur le risque de contrepartie dans les secteurs les plus sensibles.

Au total, l’impact instantané des scénarios de transition sur les 6 principaux établissements bancaires atteint 160 millions d’euros en cas de transition accélérée et 69,6 millions en cas de transition retardée. Les pertes enregistrées sont donc relativement modestes par rapport à un stress-test standard tel que ceux habituellement mis en œuvre par l’EBA. Au final, c’est essentiellement sur la partie souveraine, en raison des scénarios de taux très adverses et de l’application des benchmarks, que porte l’impact total (-198,8 millions d’euros dans le scénario de transition accélérée).

2.3. Synthèse analyse du risque de transition énergétique

Au final, l’exercice pilote révèle donc une exposition globalement « modérée » des banques et des assurances françaises au risque de transition climatique. Cette conclusion doit être cependant relativisée à l’aune des incertitudes portant à la fois sur la vitesse et l’impact du changement climatique. Elle est également contingente aux hypothèses, aux scénarios analysés et aux difficultés méthodologiques soulevées par l’exercice. En outre, si cette analyse intègre bien les interactions sectorielles et le risque d’une dévaluation importante, voire massive, du prix de certains actifs, elle ne tient pas compte des risques de contagion, de rupture des chaines d’approvisionnement ou d’amplification observés généralement lors des épisodes de tensions ou de crises financières. Ces estimations constituent donc un minorant des risques financiers. Enfin, dans l’interprétation de ces résultats, il convient de garder en tête que les scénarios analysés n’induisent pas de récession économique à l’horizon 2050, contrairement à la pratique usuelle des stress-tests de l’EBA, mais, pour les scénarios adverses, une moindre croissance de l’activité

3. Analyse du risque physique

3.1. Analyse du secteur assurance

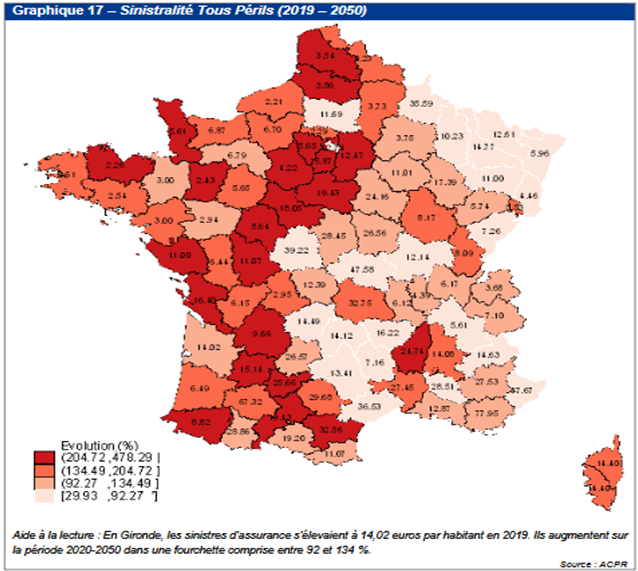

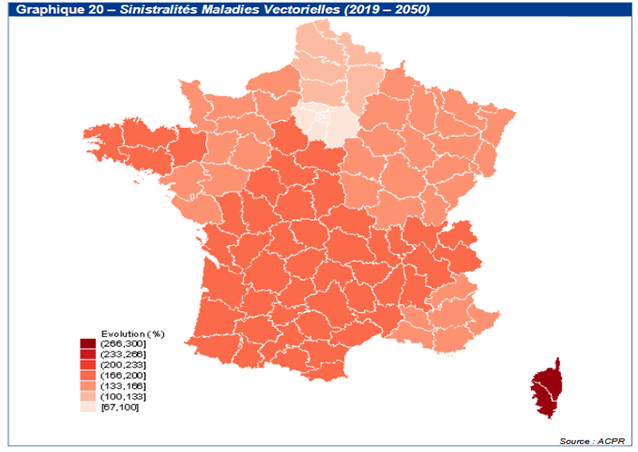

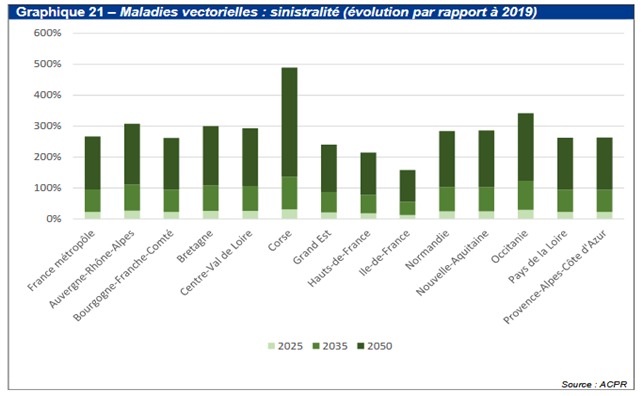

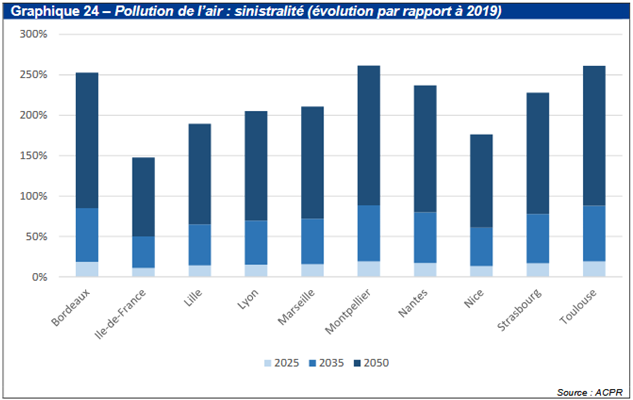

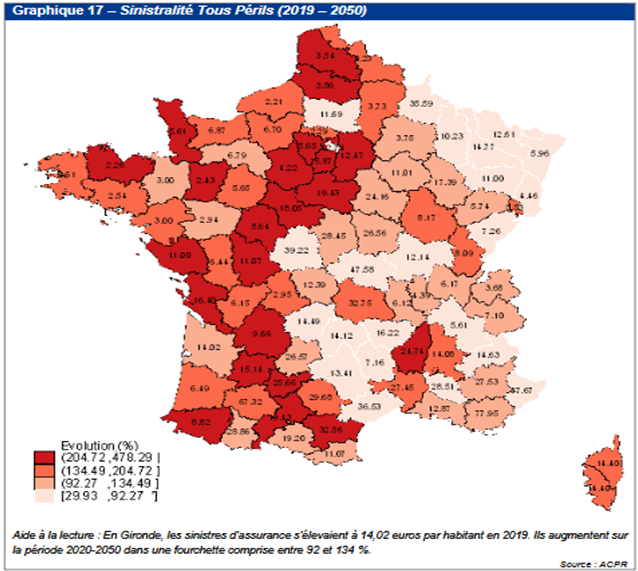

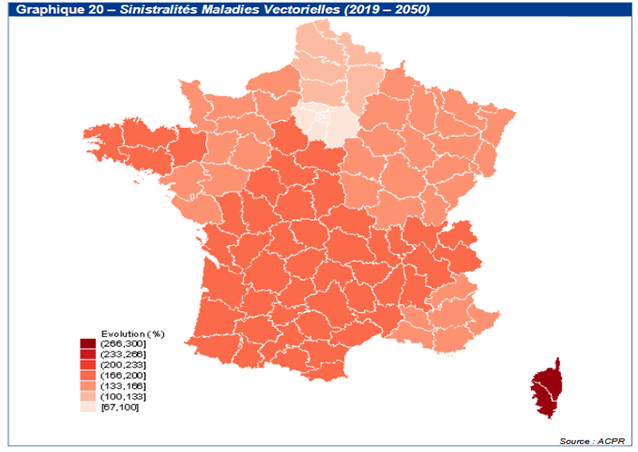

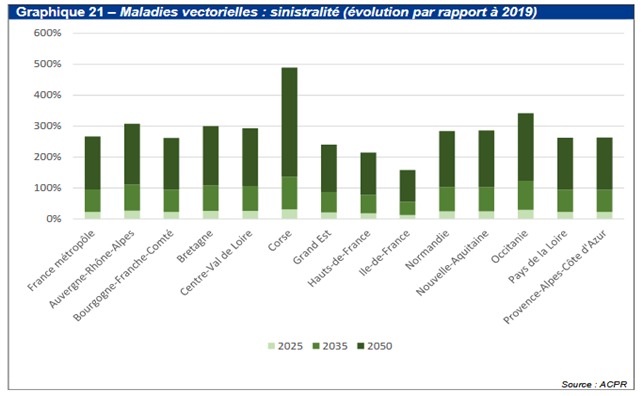

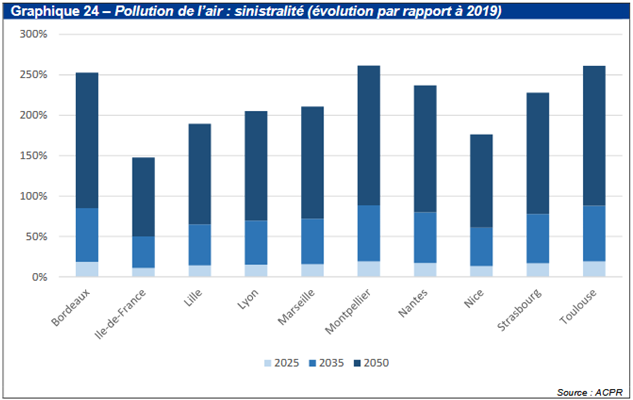

Le risque physique étudié dans cet exercice repose sur les hypothèses suivantes :

- L’augmentation de la fréquence et du coût des évènements climatiques extrêmes en raison du réchauffement climatique.

- La propagation de maladies / pandémies vectorielles et de pathologies respiratoires induites par l’augmentation des épisodes caniculaires et de leur durée et transitant notamment par un accroissement de la pollution de l’air. Ces événements sont de nature à avoir des conséquences sur les biens et les personnes. Les activités d’assurance sont ainsi impactées en premier lieu par ces changements et seuls les assureurs ont eu à appliquer ces scénarios sur leurs engagements non-vie.

Le scénario suppose une hausse des températures comprise entre 1,4°C et 2,6°C en 2050. Il s’agit du scénario le plus pessimiste retenu par le GIEC.

3.2. Analyse du secteur bancaire (risque indirect)

Outre le risque opérationnel généré par le risque physique, les banques ont été sensibilisées à deux sources de risques potentielles supplémentaires.

3.2.1. Portefeuilles garantis par un bien immobilier (ménage et entreprise)

L’impact d’une plus grande probabilité d’occurrence d’évènements climatiques extrêmes (submersion marine, inondation et sécheresse – pouvant impacter la valeur des biens immobiliers avec par exemple le gonflement des sols argileux) sur le risque de crédit, se matérialisant par la dépréciation du prix du bien garanti dans les zones à risques et donc un accroissement éventuel de la perte en cas de défaut (LGD). À cet effet, s’ajoute pour les ménages une hausse éventuelle de la probabilité de défaut (et de LGD) en cas de diminution de la protection assurancielle des ménages emprunteurs.

3.2.2. Portefeuille entreprises (secteurs vulnérables)

Outre les canaux de transmission décrits ci-dessus, les établissements étaient invités à prendre en compte l’impact sur l’activité de ces évènements (interruption d’activités, pertes de récoltes, désorganisation de la chaîne d’approvisionnement etc.) qui pourraient conduire à une baisse du chiffre d’affaires et de la valeur ajoutée pour les contreparties à risques, ce qui pourrait se traduire par une hausse de la probabilité de défaut.

4. Synthèse générale

4.1. Des résultats du pilote globalement encourageants

L’exercice pilote révèle une exposition globalement « modérée » des banques et des assurances françaises aux risques liés au changement climatique.

Sur la base des structures actuelles de bilan, il apparaît néanmoins que des efforts importants sont à fournir en vue de contribuer à réduire significativement les émissions de gaz à effet de serre à l’horizon de 2050 et à contenir ainsi la dynamique des températures d’ici la fin du siècle.

L’exposition des institutions françaises aux secteurs les plus impactés par le risque de transition, tels qu’identifiés dans cet exercice (industries extractives, cokéfaction et raffinage, pétrole, agriculture, etc.), est relativement faible.

Même si la France est relativement épargnée dans les scénarios du GIEC, l’exercice pilote montre que les vulnérabilités associées au risque physique sont loin d’être négligeables. Ainsi, sur la base des éléments remis par les assureurs, le coût des sinistres pourrait être multiplié par 5 à 6 dans certains départements français entre 2020 et 2050.

4.2. Les limites de l’exercice conduisant à nuancer les résultats obtenus

Cette conclusion de l’étude doit être cependant relativisée à l’aune des incertitudes portant à la fois sur la vitesse et l’impact du changement climatique. Elle est également contingente aux hypothèses, aux scénarios analysés et aux difficultés méthodologiques soulevées par l’exercice.

En effet, cet exercice fait apparaître un certain nombre de limites méthodologiques sur lesquelles il est nécessaire de progresser. Les principaux points d’amélioration identifiés par l’ACPR portent sur :

- Les hypothèses retenues pour la confection des scénarios et l’identification des secteurs sensibles.

- La difficulté de prise en compte du « risque physique », notamment pour le portefeuille « entreprises ».

- L’amélioration des modèles utilisés par les établissements bancaires ou les organismes d’assurance et des sources de données.

4.3. La feuille de route des institutions financières

Les institutions bancaires et les assureurs doivent donc approfondir dès aujourd’hui leurs actions en faveur de la lutte contre le changement climatique, en intégrant les risques induits par ce dernier dans leur processus d’évaluation des risques financiers, car ce sont ces actions qui contribueront aux évolutions observables à moyen et long terme. Cette meilleure prise en compte du risque de changement climatique est en effet nécessaire pour favoriser une meilleure allocation des ressources et assurer le financement de la transition.

5. Références

https://acpr.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/20210602_as_exercice_pilote.pdf

Abréviations et gLossaire

EBA: European Banking Authority[:en]Note: the main text is taken from the ACPR report mentioned in the reference. This article aims to highlight some extracts from this report in order to better understand the essence of the study.

1. ANALYSIS of financial risks due to climate change

From July 2020 to April 2021, the ACPR conducted a pilot stress test exercise on the impact of climate change (physical and transitional risks) on the financial risks of the financial sector. The exercise involved players from banking and insurance groups.

The horizon over which risks are assessed is 30 years and several scenarios have been implemented on different economic sectors in a dynamic vision of the balance sheets of financial institutions. This work is part of the implementation of the fight against climate change and the promotion of energy transition and green growth, in line with the Paris Agreement in 2015.

This exercise to assess the financial risks induced by climate change will be repeated regularly. The next ACPR exercise is expected to take place in 2023/2024.

2. Impact analysis of energy transition risk

2.1. Three Energy Transition Stress Tests Scenarios

The transition scenarios include a reference scenario, corresponding to an orderly transition, and two disordered transition scenarios.

The reference scenario chosen by the ACPR is the most favourable scenario, although it is already based on a significant increase in the price of carbon, leading to major changes in the economy.

The first adverse scenario of a disorderly transition is that of a late transition. It assumes that the greenhouse gas emission reduction target is not met by 2030, requiring more aggressive measures to be put in place. It assumes that carbon sequestration technologies are less effective than expected in offsetting emissions. It is based on the assumption that the price of carbon will rise sharply in 2030 in order to maintain the objective of carbon neutrality in 2050. The price of carbon rises from $14 per tonne of CO2 at the global level in 2030 to $704 in 2050. This increase results in a series of heterogeneous shocks on the sectors of activity and leads to a very strong increase in real energy prices (+125%) over this period in France.

The second adverse scenario of disordered transition is that of an accelerated transition. It combines a strong increase in the price of carbon, which reaches $917 per ton of CO2 in 2050, and a less favourable evolution of productivity than that assumed in the reference scenario from 2025. In addition, renewable energy technologies are less efficient than expected, which implies higher energy prices and additional investment needs.

The different results are shown below.

2.2. Results of the energy transition stress tests

2.2.1. Dynamic balance sheet

The dynamic balance sheet hypothesis allows institutions to make management decisions in response to the various scenarios analysed and to reallocate their business portfolio among the various sectors of activity from 2025 onwards. This hypothesis makes it possible to analyse the long-term strategies deployed by institutions.

The “electricity and gas” sector, which benefits from the transition in the scenarios, has seen its share of total exposures rise sharply, while at the same time the extractive industries sector, which is negatively impacted, has seen its share of banks’ corporate exposures decline.

Two main types of strategies appear:

- Some institutions choose to finance the economy as a whole by aligning the structure of their loan portfolio with the sectoral structure of the economy. However, it cannot be entirely ruled out that this choice reflects a passive adaptation strategy. It is also possible that this choice is the result of the difficulty some institutions have in deciding on strategic management actions over such a long time horizon.

- Those of the banks that have conducted a sector-by-sector analysis, in order to choose the reallocations to be made on a more detailed basis. This choice may be conditioned by:

- The existence of public commitments or a sectoral policy already decided.

- The desire to support key sectors in the energy transition.

- Pressure from civil society to reduce certain sectoral exposures.

- A divergence in the analysis of sectoral dynamics by 2050 with the scenarios provided by the ACPR.

2.2.2. Credit risk

The analysis focuses on credit risk projections under the different transition scenarios. The indicator used is the annual cost of credit risk. The latter is calculated by dividing the total annualized provision flows for each time interval by the average of the exposures over that same time interval. The figures presented correspond to the aggregate of the 6 main French banks participating in the exercise.

In the accelerated transition scenario, the annual cost of credit risk is 17.2 bps in 2050 compared to 15.8 bps in the orderly transition scenario (+ 8.9%).

The analyses tend to confirm that a disorderly transition (and even an orderly transition) has a significant impact on banks’ credit risk. However, the magnitude of this impact appears to be smaller than that observed in the EBA’s biannual stress-testing exercises. This is because none of the transition scenarios considered is accompanied by a decline in GDP, unlike the usual regulatory stress-testing framework.

Sectors sensitive to the energy transition are represented by the sectors:

- Crop and animal production, hunting and related services.

- Extractive industries.

- Coking and refining.

- Chemical industry.

- Manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products.

- Metallurgy.

- Wastewater collection and treatment, collection, treatment and

- Waste disposal, remediation and other waste management services

The sectors of interest in relation to the energy transition are represented by the sectors:

- Food industries, beverage manufacturing, tobacco product manufacturing

tobacco products. - Manufacture of rubber and plastic products.

- Manufacture of fabricated metal products, except machinery and

- Automotive industry.

- Production and distribution of electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning.

- Construction.

- Sale and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

- Wholesale trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

- Retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

- Land and pipeline transport.

- Air transport.

- Accommodation and catering.

- Administrative and support service activities.

Note: The triangle represents the total rate of change (in%) of the cost of corporate risk between the two limits studied. Each part of the histogram then represents the variation (%) induced by the different sets of sectors.

The reading of this graph is as follows: the left part represents the dynamics of the cost of risk between 2025 and 2050 in the scenario orderly transition; the part on the right represents the additional effect of a disorderly transition (i.e., the cost of corporate risk observed at end of 2050 in the accelerated transition scenario). This cost is 12.2% higher than that observed in the orderly transition scenario to same date.

Note: the graph above represents the weighted average (by the exposures for each sector) of the on year probabilities of default by sector of the 6 main French banking groups.

2.2.3. Market risk

Market risk is the second category of risk for which banks project losses. It is broken down into two sub-categories:

- The revaluation of the trading portfolio, following an instantaneous market shock induced by the valuation of assets on the basis of anticipated transition scenarios.

- The impact of these market shocks on counterparty risk in the most sensitive sectors.

In total, the instantaneous impact of the transition scenarios on the six largest banks amounts to 160 million euros in the case of an accelerated transition and 69.6 million in the case of a delayed transition. 69.6 million in the case of a delayed transition. The losses recorded are therefore relatively modest compared with a standard stress test such as those usually implemented by the EBA. In the end, the total impact is mainly on the sovereign part, due to the very adverse interest rate scenarios and the application of benchmarks (-198.8 million euros in the accelerated transition scenario).

Note: on the left, the impact on the fair value of the trading book, on the right on the counterparty risk. On the left graph, the consequent impact of interest rate positions is not included because this complicates the reading of the results without these instruments being particularly related to the analysis of transition risk. Sensitive exposures are isolated (they do not sit with the others contributions) and correspond to equity and bond type instruments in the 6 sensitive sectors identified in the exercise template (A01, B, C23, C24, E37-37) based on the magnitude of market shocks

2.3. Summary analysis of the energy transition risk

In the end, therefore, the pilot exercise reveals an overall “moderate” exposure of French banks and insurance companies to climate change risk. However, this conclusion must be put into perspective in light of the uncertainties surrounding both the speed and the impact of climate change. It is also contingent on the assumptions, the scenarios analysed and the methodological difficulties raised by the exercise. Moreover, while this analysis does take into account sectoral interactions and the risk of a significant, even massive, devaluation of the price of certain assets, it does not take into account the risks of contagion, disruption of supply chains or amplification generally observed during episodes of tension or financial crises. These estimates are therefore a floor of the financial risks that may actually occur. Finally, when interpreting these results, it should be borne in mind that the scenarios analysed do not lead to an economic recession by 2050, contrary to the usual practice of EBA stress tests, but, for the adverse scenarios, to lower growth in activity

3. Physical risk analysis

3.1. Analysis of the insurance sector

The physical risk studied in this exercise is based on the following assumptions:

- The increased frequency and cost of extreme weather events due to global warming.

- The spread of vector-borne diseases/pandemics and respiratory pathologies induced by the increase in heat waves and their duration, notably through an increase in air pollution. These events are likely to have consequences for property and people. Insurance activities are thus primarily affected by these changes and only insurers have had to apply these scenarios to their non-life commitments.

The scenario assumes a temperature rise of between 1.4°C and 2.6°C in 2050. This is the most pessimistic scenario retained by the IPCC.

Note: In Gironde, insurance claims amounted to 14.02 euros per inhabitant in 2019. They are increasing on the period 2020-2050 in a range between 92 and 134%.

3.2. Analysis of the banking sector (indirect risk)

In addition to the operational risk generated by physical risk, banks have been made aware of two additional potential sources of risk.

3.2.1. Portfolios secured by real estate (household and business)

The impact of a greater probability of occurrence of extreme climatic events (marine submersion, flooding and drought – which can impact property values with, for example, the swelling of clay soils) on credit risk, materialising in the depreciation of the price of the guaranteed property in high-risk areas and therefore a possible increase in the loss given default (LGD). This effect is compounded for households by a possible increase in the probability of default (and LGD) if borrowing households’ insurance protection is reduced.

3.2.2. Business portfolio (vulnerable sectors)

In addition to the transmission channels described above, institutions were asked to take into account the business impact of these events (business interruption, crop losses, supply chain disruption, etc.), which could lead to a decline in turnover and value added for risky counterparties, which could result in an increased probability of default.

4. General summary

4.1. Overall encouraging results from the pilot

The pilot exercise reveals an overall “moderate” exposure of French banks and insurance companies to climate change-related risks.

On the basis of the current balance sheet structures, it nevertheless appears that major efforts are required to contribute to a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and thus to contain the temperature dynamics by the end of the century.

The exposure of French institutions to the sectors most affected by transition risk, as identified in this exercise (mining, coking and refining, oil, agriculture, etc.), is relatively low.

Even if France is relatively spared in the IPCC scenarios, the pilot exercise shows that the vulnerabilities associated with physical risk are far from negligible. Thus, on the basis of the information provided by insurers, the cost of claims could be multiplied by 5 to 6 in certain French departments between 2020 and 2050.

4.2. the limitations of the exercise leading to nuances in the results obtained

However, this conclusion of the study must be put into perspective in view of the uncertainties concerning both the speed and the impact of climate change. It is also contingent on the assumptions, the scenarios analysed and the methodological difficulties raised by the exercise.

The exercise revealed a number of methodological limitations that need to be addressed. The main areas for improvement identified by the ACPR relate to:

- The assumptions used to create the scenarios and identify the sensitive sectors.

- The difficulty of taking into account “physical risk”, particularly for the “corporate” portfolio.

- Improving the models used by banks or insurance companies and the data sources.

4.3. The roadmap for financial institutions

Banking institutions and insurers must therefore step up their efforts to combat climate change today by integrating climate change risks into their financial risk assessment process, as these actions will contribute to observable changes in the medium and long term. This better consideration of climate change risk is indeed necessary to promote a better allocation of resources and ensure the financing of the transition.

5. References

https://acpr.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/20210602_as_exercice_pilote.pdf[:]